7 years ago

7 years ago

Make Your Own Career #1

Over the course of November I’m freelancing at Bath Spa University running a series of events on enterprising career paths.

Bath Spa University has a vested interest in supporting enterprising students for several key reasons:

- They have a higher than average number of students in self-employment 6 months after graduation (12-14% compared to nationally 5-6% according to DLHE data), this is linked to…

- Like a lot of Arts Schools they have a lot of degree programmes that lead up to the creative industries as a sector, which is increasingly ‘precarious’ and dominated by contracting, portfolio working, and freelancers.

- Student interest in entrepreneurship of all forms continues to swell year on year with more seeing it as a viable career pathway.

So this autumn we have a 3-part series on different strands of enterprising careers, starting with Freelancing. The essential structure is one or more workshops led by experts plus good Q&A opportunities for the students to engage and network. The events are supplemented by great resources on the BathSparks web-page (locked inside the Bath Spa intranet - sorry!) and further prompts and tools shared via social media.

For this event I enlisted a couple of real experts in starting out and managing a freelance career: Philiy Page of Creative Women International and Helen Forsyth of Find a Creative Pro whose shared insights and advice I’ve tried to summarise below:

Be a Brand.

As an emerging freelancer its difficult to stand out and establish credibility - you may have little professional work to shout about. You need to think like a brand and establish yourself as a leader in your field - can you establish credibility and leadership by developing and recording personal projects, volunteering your services to charities, critiquing others, writing reviews, or curating good content?

The Banana Test.

You will need to hone how you pitch what it is you do - and the value that you can provide for a client. Can you articulate your pitch written on a banana? If it doesn’t fit it is too long!

Mastermind Groups.

It really helps at the early stages to have some peer support, can you gather some people going through the same process as you to kick ideas around with you and share experiences?

Six Degrees of Separation.

Supposedly we’re all connected by just six connections (according to LinkedIn I know someone who knows someone who does in fact know Kevin Bacon) - make the most of your own networks and those of your friends to identify dream clients.

Brief well

Managing expectations is critical for freelance work - do you and your client actually understand the outcomes and process that you’ve agreed to? Is there any chance of misunderstanding and confusion? Be clear about outcomes, timelines, costs, processes, and communications.

Get a contract EVERY time.

Contracts set down those expectations and clarify agreements in case of future dispute. Whilst it might feel extreme even a simple contract can make a world of difference, and its professional! Even casual work for friends should be bound by contract, just in case.

Communicate professionally.

Pick the right methods (email, phone, face to face) and try not to find yourself communicating by snapchat in the small hours of the morning, or via Facebook where clients can also see your holiday photos. Be professional and set the tone. Tools like Slack and Basecamp can be good options.

7 years ago

7 years ago

Unbundling Higher Education

A couple of months back I found this Forbes article on the impacts of innovation on Higher Education.

Given I now teach in a Centre for Innovation it looked like the kind of thing I should be reading - it’s not about teaching innovation, it’s about how innovations in and around HE are impacting on our model of what HE is, what it does, and how our ‘consumers’ engage with us. Whilst I personally find much of the 'consumerisation’ of HE dispiriting and soul-destroying I can easily recognise the impacts of the trends towards individualisation, return on investment, and commodification outlined in the discussion framed by the article.

One particular idea struck me powerfully - this 'unbundling’ of the degree model; at the moment students still 'buy’ a 'package’ from a university that includes both tutelage, certification, and access to a huge array of support services (accommodation, IT, study support, welfare, careers advice, extra-curricular activity etc) most of which is still 'bundled’ into the course fee. However the future model might separate these elements out; a student might assemble their degree from units or modules taken at a dozen or more institutions via remote means, like buying single tracks rather than an album. They might not 'need’ many of the packaged extras, or they may decide they don’t need to pay for them… why pay for welfare services or study support if you’re not studying 'at’ a specific institution?

This kind of opportunity would apparently suit many young people; a lower-cost, more bespoke, more flexible, less structured model that means you could study almost any course from anywhere in the world. It would render a lot of the infrastructure (and jobs) that universities have amassed for years unnecessary and unaffordable if it became the standard model for degree study - so this represents a huge challenge for universities and one that they will resist.

However unless every HE institution resists, and unless the private sector is forcibly kept out, then this model will emerge as students vote with their feet. In the current situation in the UK you can easily foresee that private organisations will move into the HE market with a niche offer of specialist online or blended learning offers and start picking up students via a 'pick and mix’ model of programmes. HE is a market ripe for disruption because of the scale of vested interests in a model that is largely unchanged for decades if not centuries. Institutions with prestigious names and reputations may well be able to mop up online students to supplement their income from traditional students and 'lesser’ institutions will fade or downsize and further compound their financial models as students elect for flexible alternatives.

To quote the article’s opening paragraph: “What does it really mean to be “educated”? And what is the role of institutions of higher education? Are our universities institutions of vocational training, funded to prepare students for jobs? Or are they institutions whose purpose is something a bit higher than that, perhaps loftier? Or both? Or neither?”

All this talk of an unbundled experience suggests to me that Universities and the school system that feeds them need to articulate a stronger argument and more explicitly framed about a 'bundled’ approach to Higher Education - the whole student experience, not just the course. It should serve as a compelling case for the importance of extra-curricular activities and a participatory experience - not just a consumerist approach to academic content. Universities have to turn that amassed infrastructure from being an expensive millstone into an unassailable advantage that entrants to the market cannot compete with.

However, the challenge of price remains; just because the 'going away to university’ for the 'bundled’ experience might be more developmental doesn’t make it affordable. We should all be worried that HE might again become a bastion of privilege for those who can afford it. If HE is reduced to a purely 'return on investment’ model for students, how do we encourage them to value the whole of the experience and not just the degree certificate itself? We already know that employers want a more rounded individual to emerge, which has to be about more than just an assembling of curricular credits?

A purely economic argument about the value of Higher Education for either an individual student, or the country as a whole, is missing most of the value of Higher Education: its about developing intelligent, creative, cultured generations of young people who add not just to the financial bottom line of the country, their employers, and their own bank accounts - but add social, cultural, creative, artistic, and scientific value too. Much of that development happens in the holistic experience of Higher Education.

Almost 20 years ago when I was an undergraduate I remember that many students even then disappeared every weekend from campus to go home to work to pay for their studies - or simply to retreat back to the comfort of home. Even then I was convinced they were missing out on the university experience - they felt less bonded, less engaged and immersed in the experience. I still think its a shame that Higher Education is thwarted in its transformational value by economic pressures.

7 years ago

7 years ago

Segmenting Student Attitudes to Entrepreneurship & Freelancing

Just before I left my role as Head of Enterprise & Employability at Bath Spa University I sat down with a colleague (Ben Franks, now running his start-up Novel Wines) and tried to segment different student attitudes to our enterprise, entrepreneurship, and freelance support offer. It’s a little crude but it really helped us check that we were covering all of the bases with our attempts to promote our work.

I chatted to a couple of people about this at IEEC who suggested it might be interesting to share - so here’s a link to a googledoc version on which you can leave suggestions should you so wish…

So whether you’re struggling with ‘self-identified start-up entrepreneurs’, ‘Likely but resistant freelancers’, or ‘the meek and institutionalised’ we’ve started to try and reach out to them…

7 years ago

7 years ago

The quest for authenticity

I’m on the train back from this year’s International Enterprise Educators Conference (IEEC) as inspired, challenged, and intimidated by the practice of my peers as ever.

One persistent theme this year for me was the continued pursuit of ever more authentic educational delivery, assessment, and contextualisation. One student was absolutely convinced this should start from day one year one and I found this a bit challenging if I’m honest. The student seemed to equate authenticity with industry briefs, client work, and similar - and delivered from the first day of study.

Authenticity is important; it’s attractive to students, parents, and employers as a potential head-start for graduate employment, it gives content more credibility and legitimacy, and it creates opportunities for industry to play a role in the educational pathway that might lead someone to their door in the future looking for a job.

But how authentic can we or should we make it? In practice the logistics and (time) costs of simulation and engaging industry can be prohibitive (as setting up degree apprenticeships is proving), and in principle we are still in education… If students actually wanted *authentic* they should have gone straight to the workplace!

Now direct entry to the workplace might not be an available option (rightly or wrongly), or it might not have been perceived by the student as an option (HE and FE marketing to school-leavers rather squeezes out the ‘go direct’ route) but equally there must be some value to 'less than authentic’ education as some sort of stepping stone BEFORE the actual workplace… As a safe space, as a test, as a general or fundamental grounding in something before indulging in specific practice?

Some students will seek out this stepping stone, others will see it as the only available route, others will see it as a way to keep their options slightly open whilst they explore.

The question emerging here is 'what constitutes authenticity?’ (and the answer may be different for starting student, finishing student, educator and employer). How 'real’ does it need to be?

More authentic experiences feel more satisfying and more relevant than classroom learning, but do we have any evidence they’re better at preparing students for the world of work (in general)? Does learning on the job accelerate learning or confine it to specific tasks and organisations? Does classroom-based learning help cultivate a broader and more critical approach or waste time that could be spent practising a specific process? I suspect the best option is a mix, the fundamentals leading to the specific and practical, or better still an early authentic experience which helps contextualise and make relevant the fundamentals which are then taught before practical content is returned to.

Does this mean deliberately NOT adding too much authenticity too soon? Or maybe there are specific features within authenticity that can be drip-fed into a programme? You might not let first-year students work to real live client briefs for example, but still use industry examples and have an industry judge for the assessment. You might save complex collaborative projects for later stages after skills and confidence have been built up via simpler but no less collaborative initial projects.

I’m sure finer minds than mine will have already dissected this issue - I’ll have to go and find them after I get off the train!

7 years ago

7 years ago

Cultivating Failure

One of my new colleagues at the CFI pointed me to this video by Astro Teller (what an amazing name) from Google/Aphabet’s ‘X’. Well worth watching but here’s my summary of the key ideas.

Teller suggests that every new project development includes both time that is directly productive to achieving the outcome and time spent learning stuff about how to achieve that outcome. For many of the ‘Moonshot’ projects at Google/Alphabet’s ‘X’ the learning can be 90% of the time spent on the project with only 10% of the time directly producing the outcome. He identifies ‘innovation’ as making that 90% as quick and efficient as possible - the ability to “compress” that learning to be quick and cheap is a mark of how innovative an individual or organisation can be.

As a result “fast failure” is encouraged, i.e. not dragging out failing projects but being ruthless at culling them, optimising the learning acquired, and moving onto the next project.

He then identifies a host of reasons why humans don’t like failing and especially not publicly and how they’ve built a culture that encourages learning from fast failure, builds creative confidence, and keeps them innovating.

Rewarding people for killing projects: actively celebrating individuals and teams who end a project and rewarding them with bonuses and holidays for doing so. He really stresses the importance of authentic rewards here - no amount of goodwill and certificates creates cultural norms quite like financial bonuses do.Using “pre-mortem” meetings at the start of a project to tease out the predicted reasons it will fail - and then working to mitigate or remove those risks.Acknowledging creative thought-processes (even if the idea itself stinks), it encourages people to take risks and be creative.All these ideas make sense in the context of creativity and rapid innovation - but as Teller himself acknowledges they’re a little counter-intuitive to most work and study environments where ‘failure’, criticism, and silliness are not rewarded.

This feels particularly challenging in an academic environment where we inevitably try and mark someone for getting it ‘right’, where the ego and professional reputation staked to a specific idea can make it feel like juggling porcelain, and where a slow bureaucratic process makes trial-and-error difficult to use as a development tool.

Nonetheless, I think the success or otherwise of the CfI is going to hang on how well we manage to create the right culture to empower and inspire our students. The use of experiential learning, formative assessment, reflective and portfolio assessment, and extensive collaborative working across disciplines are all at the forefront of our methodology.

7 years ago

7 years ago

Starting over

After 23 months away I find myself back at the University of Bristol, as a Teaching Fellow in the new Centre for Innovation (CfI). I’ve shifted from the professional side of HE to the academic, moved to a PT contract to accommodate some freelancing, and I’m going to update this blog once more to capture and share my learning.

Its wonderful to be in at the start of something; the CfI is currently a handful of new starters, a largely empty office floor, a name, some course descriptors, and a whole heap of aspiration and bright ideas. The new starters are intimidatingly talented, the space is huge, the ambitions are both worthy and challenging - it’s all pretty exciting really! The students start in 3 weeks!

The first challenge is turning a big white box of a space, a disparate bunch of strangers, and some aspirational documents into a living breathing thing that grows and develops innovators. We’re building an ecosystem. In my interview for this role I was quick to suggest you can’t teach entrepreneurship, but it can be learned, so you have to build an environment that stimulates, supports, challenges, and hones would-be entrepreneurs and innovators. We have to make this space, and the people in it, walk the talk.

The sense of opportunity is palpable here and its both invigorating and terrifying, as all authentic challenges should be.

My particular personal challenges here will be about rekindling ambition and shedding some cynicism. What I mean by this is that after several years on the professional side of HE, dealing with politics and bureaucracy, negotiating the accumulated inertia, I suddenly find myself in open(ish) space with time to think and create - what will I actually do with it all? I’m very used to getting “enough” done, to a “decent” quality, on the sidelines of other duties, now I have an opportunity to pour some time into this work.

Furthermore, I realise I’ve grown a little cynical about entrepreneurship and innovation; I’ve learned (after probably too many years) about opportunity cost and have become (slightly) more wary of ideas and less enthused. However, having seen some of our new students’ application videos, and the soaring optimism and inspiration on display, I will need to temper the pragmatism and tap back into my own aspiration to not shoot these fledging entrepreneurs down!

The other staff here are staggeringly talented - real commercial and industrial expertise. My own expertise as an educator, organiser, and networker feels less impressive - but I hope will be catalytic in enabling this team to thrive.

7 years ago

7 years ago

Enabling the Esoteric

(Also appears on the Create-Hub blog)

The music of massed frogs, composing for piano and grinding rocks, and an iPad-based ballet installation, one academic’s creative uses of technology might stretch your sense of the possible.

Professor Andrew Hugill is Director of the Centre for Creative Computing at Bath Spa University, and he has a long record of creative outputs in which digital technologies have played a critical role. Whilst Andrew would be at pains to suggest he does do ‘conventional’ work for serious commissions his self-initiated projects often seem to start with a 'what if…’ type provocation or curiosity-driven query into something the rest of us would regard as difficult or unlikely to produce anything of value.

My first real encounter with Andrew’s creative use of technology was featuring his Digital Opera as part of Bath Spa’s exhibits at the Bristol and Bath 'VentureFest’ at which we showcased how the kinds of creativity the university is famous for are increasingly based on digital technology. However, it was the second encounter, this time with a showcasing of 'Pianolith’ at a 'show and tell’ meeting for some of our many academic creative practitioners that I really got fascinated. 'Pianolith’ is a composition based on the duet of piano and grinding rocks… and essentially seeks to showcase that a skilled pianist can accompany something as seemingly un-musical as scraping stones. For all those of us asking 'why do this?’ Andrew’s answer was essentially 'why not - it looked interesting?’

Technology has always been an enabling tool, through the advent of new technologies we can unlock new opportunities by rendering the impossible or difficult into the possible and accessible. The development of new technologies and new uses for existing technology tends to be driven by both problem-solving approaches, “how do we solve this?” and more inquisitive approaches, “what happens if we do this?” This latter approach - the 'what if…’ approach might feel more speculative but often leads to more creative and unexpected outcomes. Both methods come into play when an individual deliberately tries to do something that no-one else had even contemplated doing… like composing for a pianist to accompany the sound of scraping stones…

Whilst the benefits were not obvious at the outset of the process Andrew has not only developed a wealth of knowledge about processing unlikely sounds into 'music’, but has provoked some major musicians into completely re-evaluating what they are able to 'accompany’: “During the recording session for Andrew Hugill’s PIANOLITH I had an extraordinary experience. The music seemed to have its own inner mind which gradually took over the performance. With every take I made, my mind became totally free. This experience moved me greatly and prompted me to seek similar qualities in other music.” (Evgenia Chudinovich, aka GéNIA) For me the instructive element was how an apparently unfruitful challenge can unleash creativity without any weight of expectation.

Profiling all of Andrew’s work would take a whole series of blogs but in a brief interview Andrew was able to share some insights into his approach to using technology as part of his creative process. Andrew crucially self-identified as an educator first and foremost, with an urge to explain and illustrate, and the research has followed later. Andrew’s personal history is littered with examples of being drawn to the difficult, unreadable, esoteric, and under-appreciated - and then trying to make sense of it to others. The challenges seem to stimulate his creativity, or maybe his urge for creative exploration draws him to the challenges…

Technology from the pencil to the computer is critical in Andrew’s work, but early experiences of computers (using punch-card machines to produce cricket scores in the 70s) must make him an early digital immigrant and enthusiast. However, Andrew credits the rise of the desktop PC in the 90s as the point at which he fully appreciated the opportunities of computers. The marriage of computing know-how and musical passion is a rich mix for creative opportunities. Andrew highlights the usefulness of the algorithmic programming process as a way to explore creativity - using a flow-diagram of 'if then…’ steps through a creative process that a machine could follow. Breaking simple tasks down into steps draws out all the fine detail of a thought process that might then be explored for creative opportunities.

Andrew’s final words of advice were not to look at the technology available now - but to try and spot the technology that will be commonplace in five years’ time - neural control, biotechnology… maybe VR will live up to the hype…

Oh yes - the 'Catalogue of Frogs’ (in which the bizarre evolutionary theories of Jean-Pierre Brisset on mankind’s evolution from frogs are rendered into music).

7 years ago

7 years ago

Personal Business Models

As part my work as a volunteer chair for the Association of Graduate Careers Advisory Services (AGCAS) we’re starting a blog on enterprise and entrepreneurship themes for colleagues working in Careers Services. This is my first contribution.

It’s becoming increasingly vital to talk to students about enterprise and entrepreneurship; more and more of them are likely to be self-employed every year, and often in industry sectors where the students heading their way are the least likely to want to talk about commercial success and business planning. I frequently find myself presenting to Artists, Musicians, and Dancers trying to persuade them that entrepreneurship is something they need to think about… Many simply avoid it, others focus in on what they feel they need to know - registering self-employed, but few initially want to tackle the really meaningful questions for success and failure like - “what are you selling?”, “who is the customer?”, “who or what are you competing against?”, “how do you make enough money?” and so on.

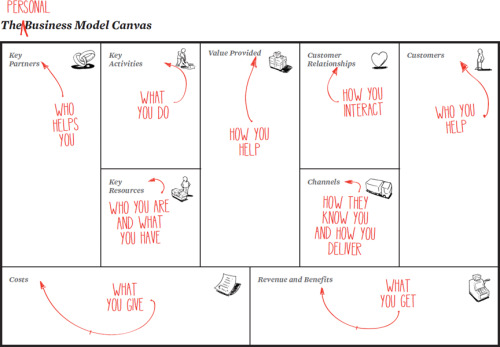

However - I have found one tool that has been really useful in unlocking some of these audiences, however hostage-like they may initially feel. The ‘Personal Business Model Canvas’ (from the book 'Business Model You’ by Tim Clark) is developed from a really well used tool called the 'Business Model Canvas’ (from the book ’Business Model Generation’ by Alex Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur). It’s a simple one-page visualisation of how a business model fits together and then adapted for thinking about a specific individual might catalyse their skills and interests to develop a sustainable business.

The various canvasses are largely available under creative commons licensing - just search for them online - although all the books are worthwhile if you get taken with the canvasses.

The beauty of the original Canvas is that you can start your planning from anywhere - by focusing on a specific customer, by harnessing a particular resource or network, by identifying a new customer-attraction or relationship management model, but usually by identifying a valuable new product or service. Once you start filling in the boxes and drawing relationships you can iterate repeatedly until it all fits together.

The Personal Business Model Canvas (PBMC) start with a focus on the individual - who are you, what are you interested in, what are you good at? (Key Resources). Then it draws out what you know how to do - roles played, professional skills, acquired knowledge and competence (Key Activities). From here you can begin to articulate how you might help others - what kinds of value can you create, what problems can you solve, how do you enhance or mitigate the issues other people or organisations face? (Value Proposition). This section is critical - the articulation of value - and I think its valuable to say out loud that its rare that anyone has a particular skill or ability that no-one else has, but the art to success is in finding the combinations of skills and experiences that make you a valuable and useful rarity.

From here we move on to 'who gets helped’ (Customers) - who needs you, to do what, are there enough of them to employ you, will they reward you? This is the great naivety check - can the student identify someone who will pay them (enough) for doing the thing they want to do? Or will they need to modify that offering to find enough customers? For more on this also check out ’Value Proposition Design’ (also by Osterwalder and Pigneur). Customers are linked to the Value Proposition by Channels ('how do people find out about you?’) and Customer Relationships ('how you interact with your customers’). These elements represent marketing, communication, distribution, networking, and retail design (online, in person, or through a third-party broker). By now, most student groups I’ve presented this to are pretty engaged, starting to ask questions and offer up ideas about how they’ll promote this new business of theirs.

Next up in the sequence is 'what you get’ (Revenues & Benefits) and 'what you give’ (Costs) and its worth spending some time here explaining that its not all about cash. Its about less tangible things like autonomy, lifestyle, work-life balance, energy, reputation and more. You do want to end up in profit - or the business is an unsustainable and expensive hobby - but there are opportunities here to think about how to make your business offer more valuable and also ways in which you can reduce costs and thus increase your profits that way. I also make a point of illustrating that if you’re passionate about a business then its less 'costly’ to you than doing something you hate. That’s why the PBMC starts with who you are - because your interests help identify business ideas that are emotionally 'cheaper’ for you to run. Likewise if you’re a shy type then a business that involves a lot of networking is going to be comparatively costly…

The final element is a great way to address many of the costs - 'who helps you?’ (Partners). The sourcing of resources and savings through partnering with others is key - access to equipment and facilities, co-promotion of services, and support and feedback. This also helps highlight to would-be freelancers and self-employed contractors that they need networks, and that they’re not alone!

From left to right the canvasses articulate how resources (interests, skills, networks) translate into a value proposition, which is then communicated (channels and relationships) to a customer - who rewards you for doing it… and hopefully the rewards on the right outweigh the costs on the left!

So far, this tool has never failed me! Its always managed to engaged even the most cynical of audiences because it marries the personal with the professional. If nothing else I always suggest its food for thought.

8 years ago

8 years ago

The Civic University

On Wednesday I had the rare pleasure of hosting Matthew Taylor, Chief Exec of the RSA, at Bath Spa University. He was with us to speak about ‘universities and place’ and the possibilities and challenges of how universities might position themselves in their locality alongside their simultaneous positioning in national league tables and international research rankings.

Matthew drew heavily on both his work with the Warwick University commission into into its civic role and on his family’s long-standing interest in the role that HEIs play in their landscape.

In a talk laced with sociological discussion he articulated his own theory of ‘social coordination’ and highlighted how HEIs had shifted over time from being highly solidaristic but insular communities into both more individualistic structures, beholden to markets, focused on innovation and enterprise, and driven by customer satisfaction, but also into authoritarian models driven by targets, rankings, and management cultures.

In the face of these individualistic and authoritarian models of motivating and organising universities we had lost much of our solidarity, much of our community. He then positioned ‘place’ as a way to regain that sense of a common cause.

Picking up John Goddard’s work on ‘Reinventing the Civic University’ he championed the idea of a ‘creative community with a cause’ and advocated cause-based leadership as a model for integrating authoritarian, solidaristic, and individualistic ways to motivate an organisation. Could ‘place’ be part of that cause? Can place be a distinctive feature for an HEI that no-one else can replicate? Can a focus on outreach and interactions stop us disappearing into our ivory towers?

His work with Warwick will advocate three main tenets of the university’s civic role:

- That the university cannot be successful itself if its place is not. A global institution cannot thrive if its staff and students are living and working in a blighted or dysfunctional locality

- That the university has to work hard to be more functional and coordinated in its civic activity, whilst “letting 1000 flowers bloom” has its merits, shouldn’t we be harnessing that activity for a greater civic impact? Functionality might include sharing more data, engaging our alumni in the issues of the region, and introducing our new students and staff not just to the university, but to their region too.

- That the university should be a platform for people to be experimental, that we should be an enabling player in the landscape, not a controlling one

He suggested we might sometimes need to be ‘creatively subversive’ in the face of local authorities who don’t understand the contribution and value of a university.

References:

Matthew Taylor blog on the Civic University

9 years ago

9 years ago

Speech to Westminster Higher Education Forum - 9/12/14

Here’s (roughly) what I said earlier at today’s #WHEFEvents Forum: